SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Editor’s note: This article appeared in the January 22, 2026 issue of the Chestnut Hill Local.

When members of the Rotary Club of Chestnut Hill describe one of their core initiatives, they are often met with skepticism.

For more than a decade, volunteers at Rotary have purchased and distributed dictionaries for third graders at public schools in Northwest Philadelphia. Known as the Dictionary Project, this initiative faces many misconceptions, according to Maggie Stoeffel, a member of the Rotary Club of Chestnut Hill.

“Anybody who first hears about this project [says] ‘A) Oh my God, what could be more boring? and B) What kid needs an actual book when everybody uses the internet to look up words?’” Stoeffel said. “Until you do this project, you just really don’t get it.”

Learning the meaning behind the Dictionary Project — and moving past that skepticism — requires a deeper understanding of the initiative’s mission.

‘Pure excitement’

The Dictionary Project began in 1992 in Savannah, Georgia, when Annie Plummer began giving dictionaries to students close to her home. As the project grew, a volunteer named Mary French decided to form a nonprofit to raise funds and coordinate distribution around the country. Since its founding in 1995, the organization has collaborated with various groups (including many Rotary clubs) to distribute more than 37 million dictionaries.

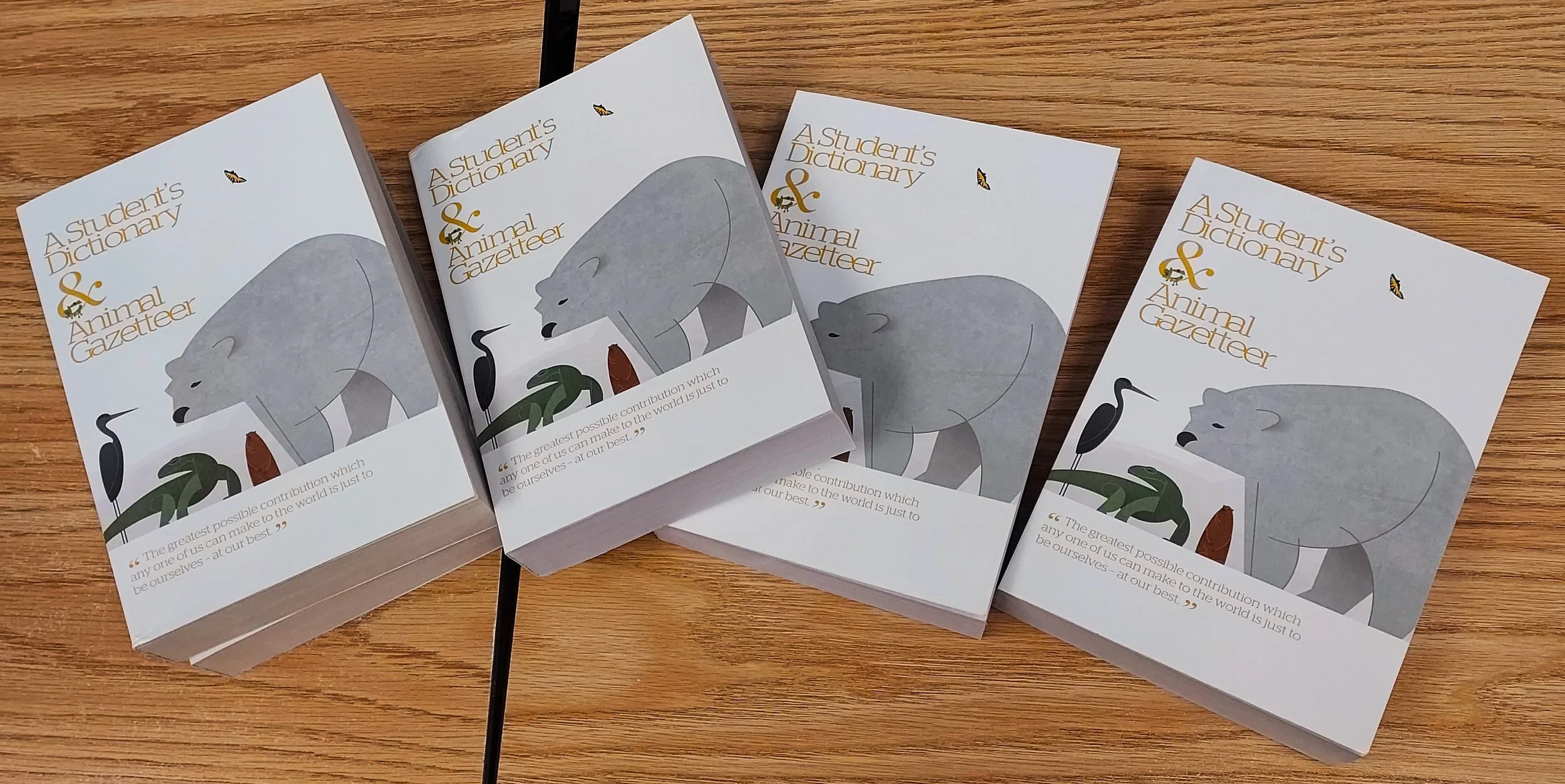

For the Rotary Club of Chestnut Hill, this project has totaled more than 3,400 dictionaries. Third graders at Eleanor C. Emlen, Henry H. Houston, J.S. Jenks Academy for the Arts & Sciences, and Anna L. Lingelbach Elementary School receive the books, entitled “A Student’s Dictionary & Animal Gazetteer.” For many students, the dictionary is the first book they can truly call their own.

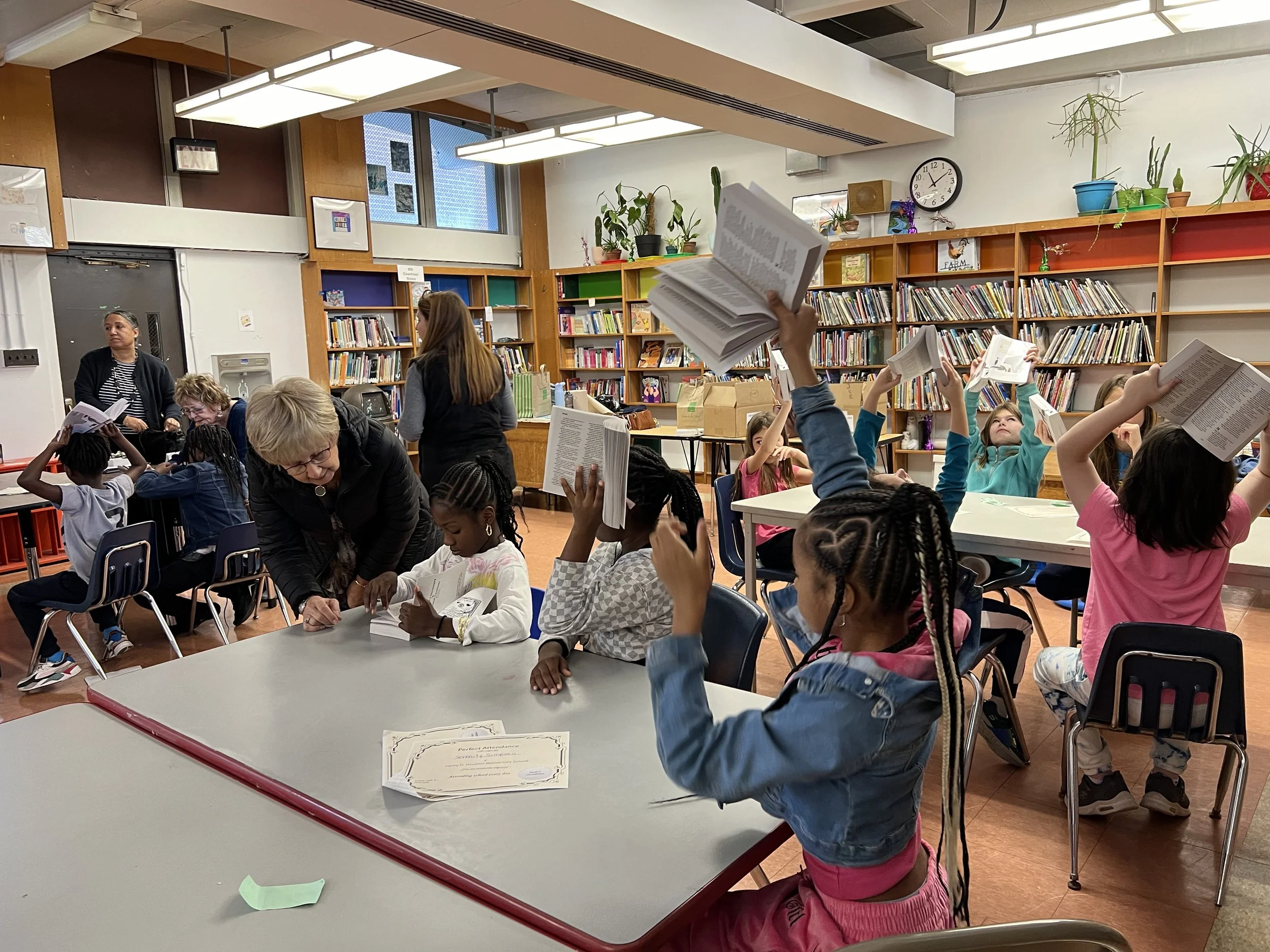

However, the dictionaries are not simply dropped off for the students. Rotary members also volunteer their time, in coordination with the schools’ principals and teachers, to engage with the students and their new books.

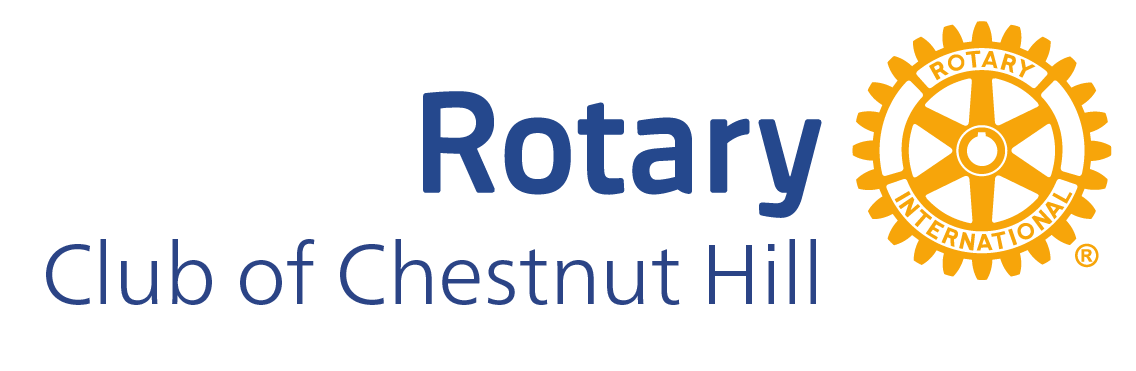

Corinne Scioli, principal at Jenks and a member of the Rotary Club of Chestnut Hill herself, said there is “pure excitement” in the room when the dictionaries are delivered.

“I often challenge the students to dive right in and find an ‘interesting fact’ to share with me,” Scioli explained. “You can see their eyes light up as they navigate the pages, racing to be the first to discover a new word or a piece of information they didn’t know before. It turns a foundational tool into a fun, interactive ‘treasure hunt.’”

The Dictionary Project website notes that the book also includes information “about the environment, facts about land and water conditions in the countries of the world, information about animals that live in nine habitats on the seven continents, information about earth and its atmosphere, the longest word in the English language, sign language and braille.”

Stoeffel recalls different prompts that Rotary members ask the students, such as finding the state bird of Pennsylvania. Then, students begin to explore on their own, sharing their findings with friends — the longest word, how to spell their names in sign language, and more.

“Starting that exploration through the book [creates] a chain reaction of engagement with the kids,” Stoffel said. “By the time our time is up, they’re all flipping through, raising their hands, finding things. Everyone who goes to do it is shocked at what a feel-good experience it is.”

Carol Bates, a member of the Rotary Club of Chestnut Hill and the Dictionary Project leader, echoes these sentiments.

“You can really feel their energy when they find something new,” Bates said. “It’s just remarkable. ‘I found it! I found it!’ They’re so excited.”

Benefits of the project

In 2026, it’s a safe assumption that most people search for definitions and other information online. Do Rotary members feel an analog method is outdated?

According to Scoili, there are still plenty of benefits to a physical dictionary.

“While we live in a digital world, a print resource encourages a different kind of focus and persistence,” Scioli said. “It serves as a tangible symbol of their growing independence as learners, reinforcing the idea that they have the power to seek out knowledge on their own.”

Scioli also believes that third grade is the perfect stage of development for this project.

“This initiative comes at a critical developmental crossroads,” Scioli explained. “In third grade, students are making the vital transition from ‘learning to read’ to ‘reading to learn.’”

In addition to all of these benefits, there remains another crucial one, according to Jay Pennie, a member of the Rotary Club of Chestnut Hill.

“The additional thing, other than the obvious having [students] learn to use a reference material for writing and learning, is that having the community come into the school and interact with the children is extremely important … because it shows that people outside of teachers and parents care about their education,” Pennie said.

Plus, students aren’t the only ones who come away from this initiative feeling fulfilled.

“Our best projects … are the ones that also transform our lives as well as the lives of those that we’re actually serving,” Stoeffel said.

To learn more, visit chestnuthillrotary.org.

Maggie Dougherty can be reached at Margaret@chestnuthilllocal.com.

If you like the great work of the Local, you may make a donation to the Chestnut Hill Local Emergency Appeal